Material Culture: Wood and Weaving

Our 2023 seasonal exhibit, Material Culture: Wood and Weaving, focused on folk art and music in our region. “Material culture” refers to the usage, construction, and traditions of objects of importance to a cultural group. The material culture of the Appalachian Forest National Heritage Area is heavily influenced by our forest landscape.

See the full exhibit panels here and photos of the exhibit here.

Folk Art

The development of folk art in this region was dependent on the environment and the available forest materials. Practices, such as weaving and basket making, that were once done for utilitarian purposes also exhibit artistic expression.

Weaving

Weaving was a necessity for families living in the isolated Appalachian mountains with little access to commercial goods. Important items for everyday life had to be woven by hand.

Historical Ties

Weaving has been practiced by many cultures all over the world for millennia. Indigenous Peoples with ancestral ties to this region include the Lenape, Seneca, and Shawnee. These groups and others were weaving long before colonial contact. As settlers migrated into what is now the AFNHA region, they brought the knowledge and skills from their homelands with them, adding to the variety of the area’s weaving traditions.

Finger Weaving

Finger weaving is a technique that evolved in several cultures around the world, including within Indigenous communities in the region. In pre-colonial times, common materials used in finger weaving included plant fibers such as milkweed fibers, the inner bark of basswood and cedar trees, nettle, and others. As colonization increased and trade became established, the native plant materials were swapped for European wool yarns.

Gradually, as the industrial revolution made textiles more readily available and new roads and technologies made it easier for people to obtain factory-made goods, home weaving became less common. Efforts such as the New Deal of the 1930s revived old crafts and traditions. More recently, hand-woven goods have become more valued for their creative handmade and historical significance than as a basic necessity of life.

Image by Gerry Milnes, courtesy of the Augusta Heritage Center.

Fibers

Before the invention of the cotton gin, wool and flax were the main fibers used for weaving. Cotton became more widespread after the 1790 invention expanded the availability of cotton trade from the south.

Processing flax was strenuous and dangerous, often taken on by both men and women. Flax fibers are spun wet. Seeds are soaked in water to create a goo-like substance that toughens the fibers so they can be spun easier.

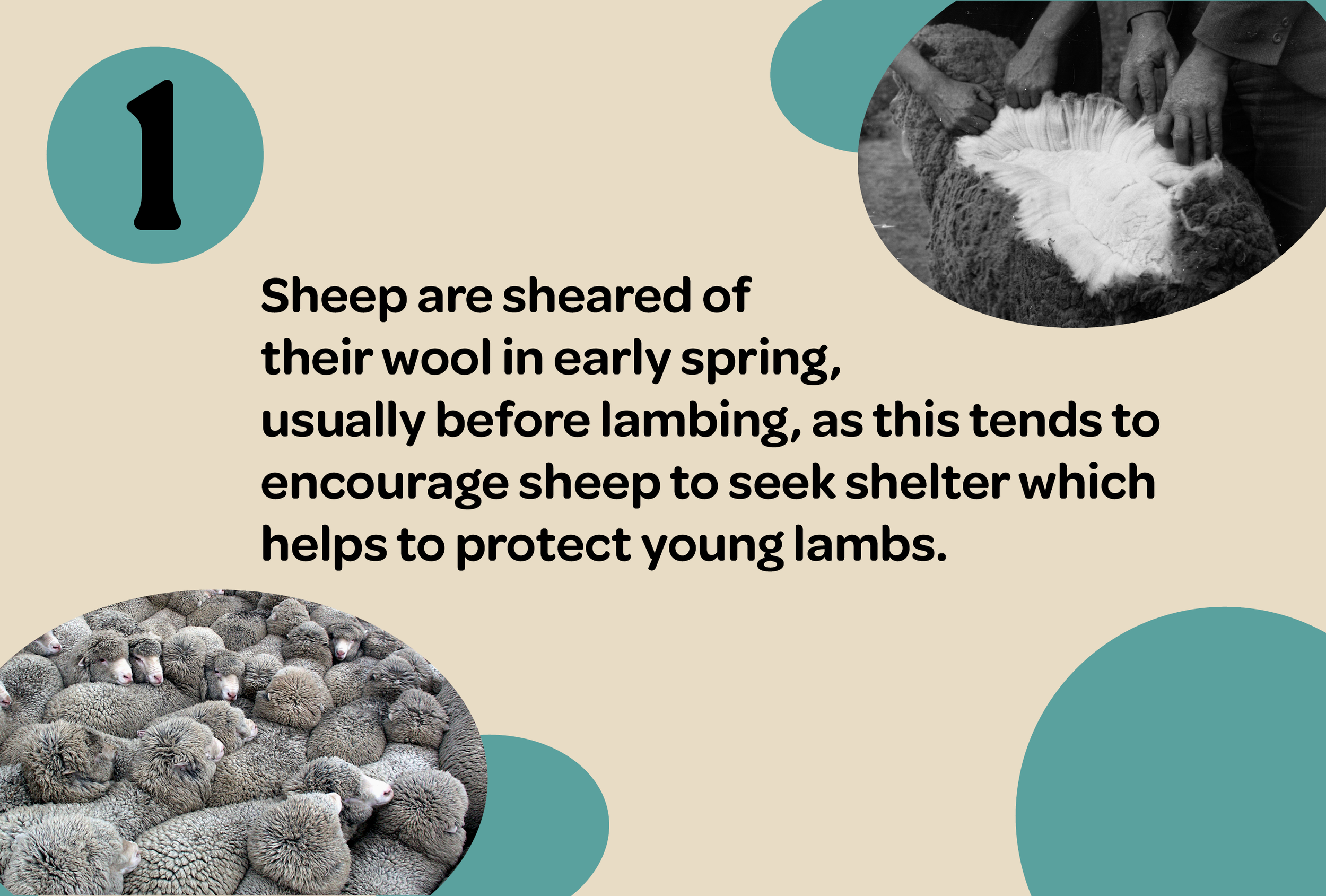

Sheep were brought into the area by early European settlers. Some of the sheep they brought were specifically chosen for the quality of their wool.

Natural Dyeing

Historically, numerous native plants have been used to dye textiles. Indigenous Peoples used hickory, sumac, poke, berries, black walnut, goldenrod, madder, and much more.

Where did it come from?

Settlers came to the area with knowledge of the dyeing process and seeds of familiar dye plants, most notably indigo for the color blue. They learned how to use the plants around them from Indigenous people and through wide experimentation. Even today, people still experiment with the dyeing process!

Making it Stick

The fiber being dyed is treated chemically through a process called “mordanting”. Mordants help the dye colors permanently set. Common mordants are alum, potassium dichromate, and tannic acid. Some mordants are hazardous and dyers must exercise caution while handling these materials.

Basketry

Appalachian baskets, rooted in practicality, are now prized for artistic value and are sentimental objects to people who grew up using them. Baskets have served many purposes throughout history from cooking vessels, to assisting farmers in planting and harvesting crops, to storing sewing materials and trinkets.

Materials

Basket making relies on the material available to the maker. Some commonly utilized trees and plants include white oak, black ash, hickory, honeysuckle, grape vines, willow, and pine needles. The sapwood (outer wood) of black ash, white ash, white oak, and other trees are split into long, thin strips of wood called splits or splints.

Traditions

Indigenous people of the area, such as the Haudenosaunee, made baskets. European settlers brought old traditions with them. Cultural diffusion between the Indigenous communities of West Virginia and White settlers allowed people to utilize and embrace all styles and technologies.

The emerald ash borer impacts tradition.

Black ash was commonly used among Northeastern Woodland Indigenous people, due to the wood’s flexibility and strength. Many Indigenous Peoples continue to make baskets and other objects from traditional materials like ash. Unfortunately, these traditions are at risk due to the invasive emerald ash borer putting a strain on the black ash population.

The Wonderful World of Wood

Trees have an important role in history and the environment. Humans have used wood for fuel, building, entertainment, tools, paper, and more.

“So perhaps this is why we take it for granted: wood has long

been a part of our lives, and we probably can’t really imagine

it not being there.”

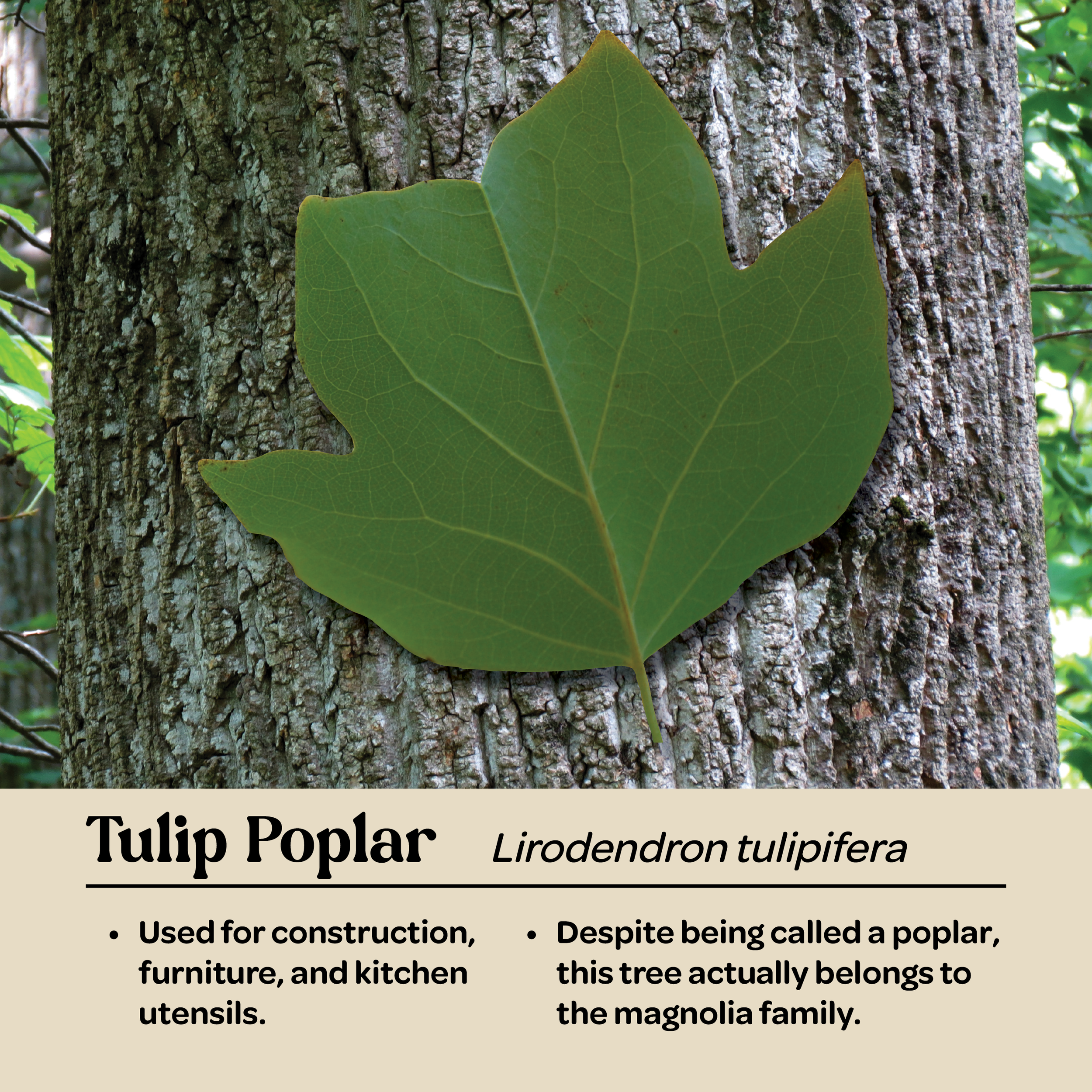

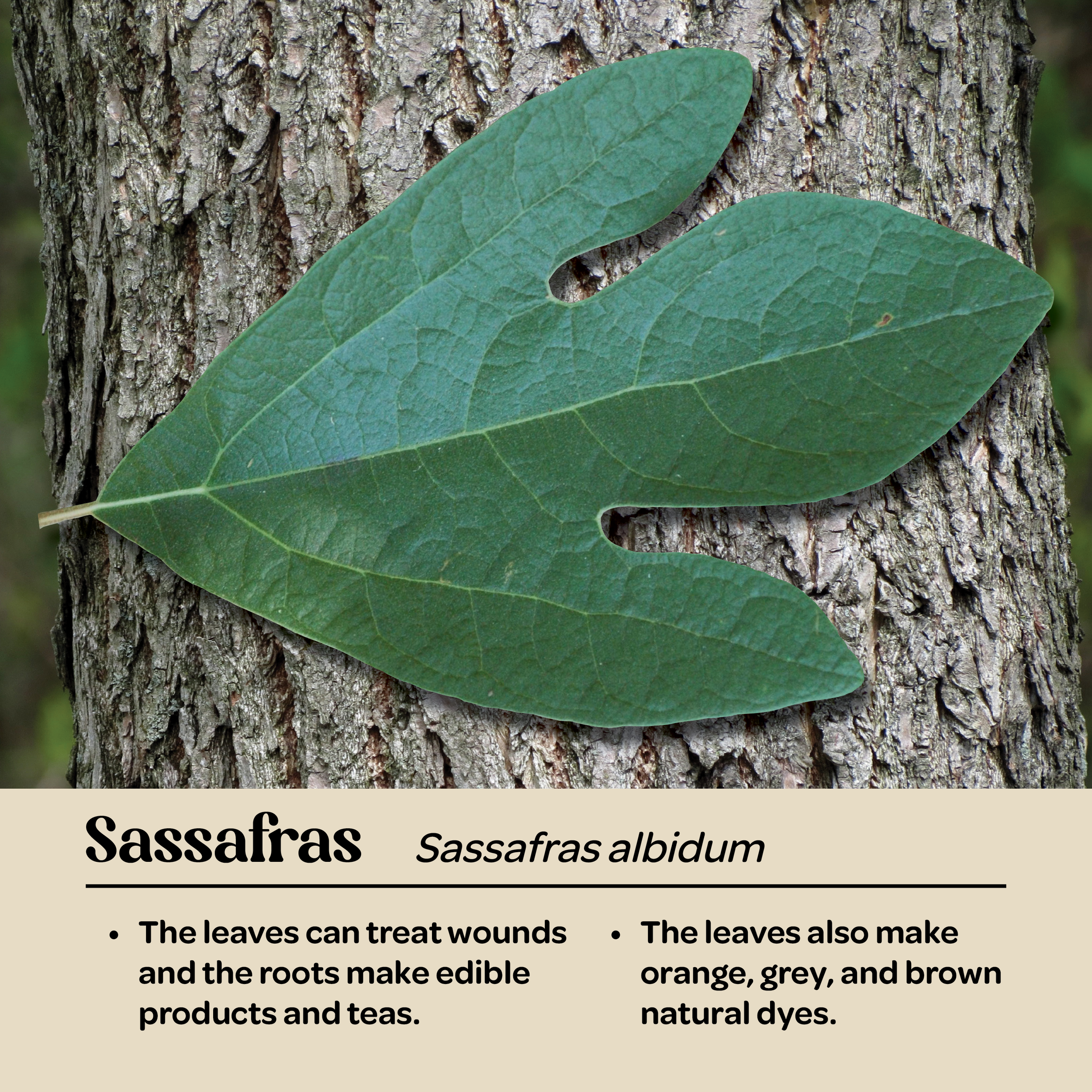

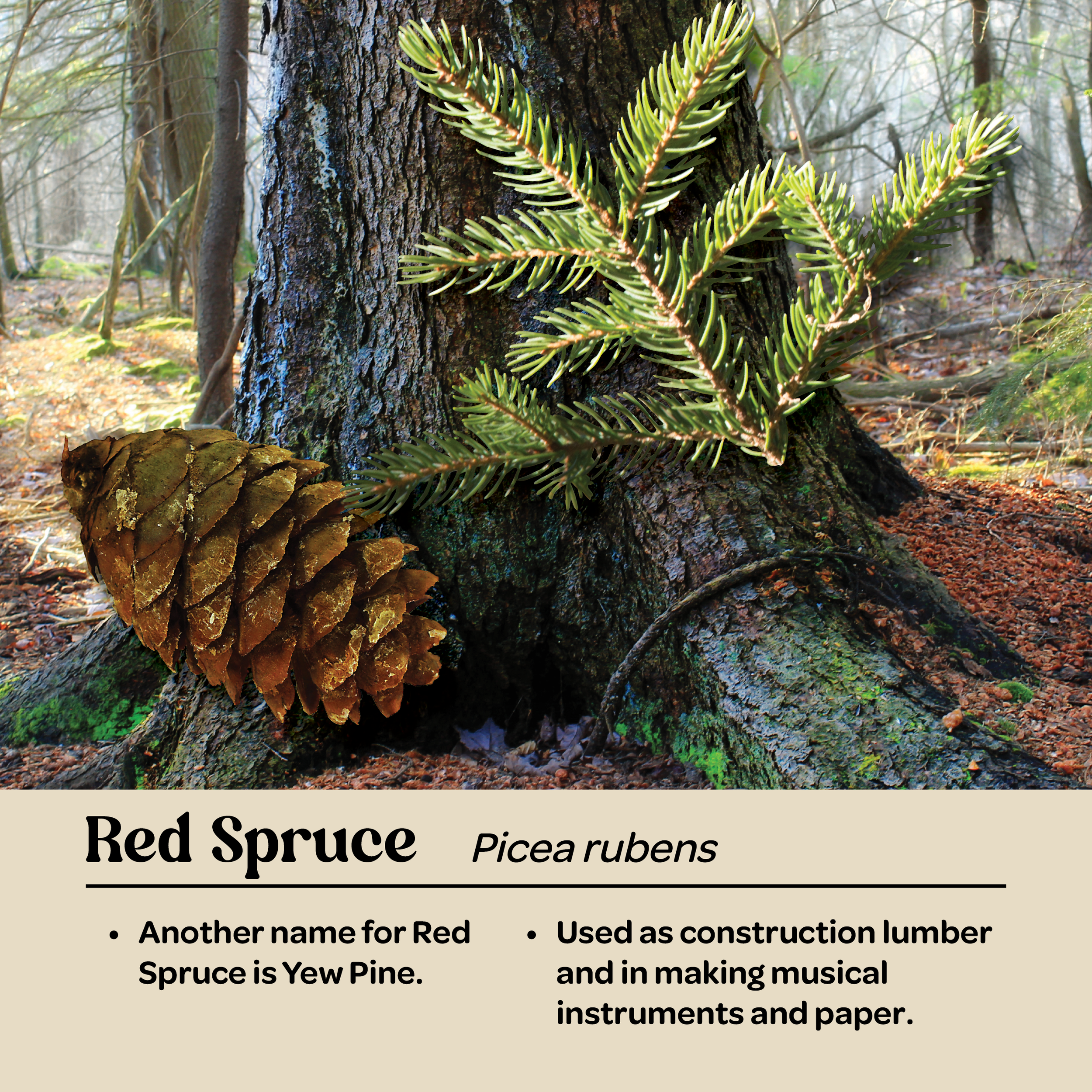

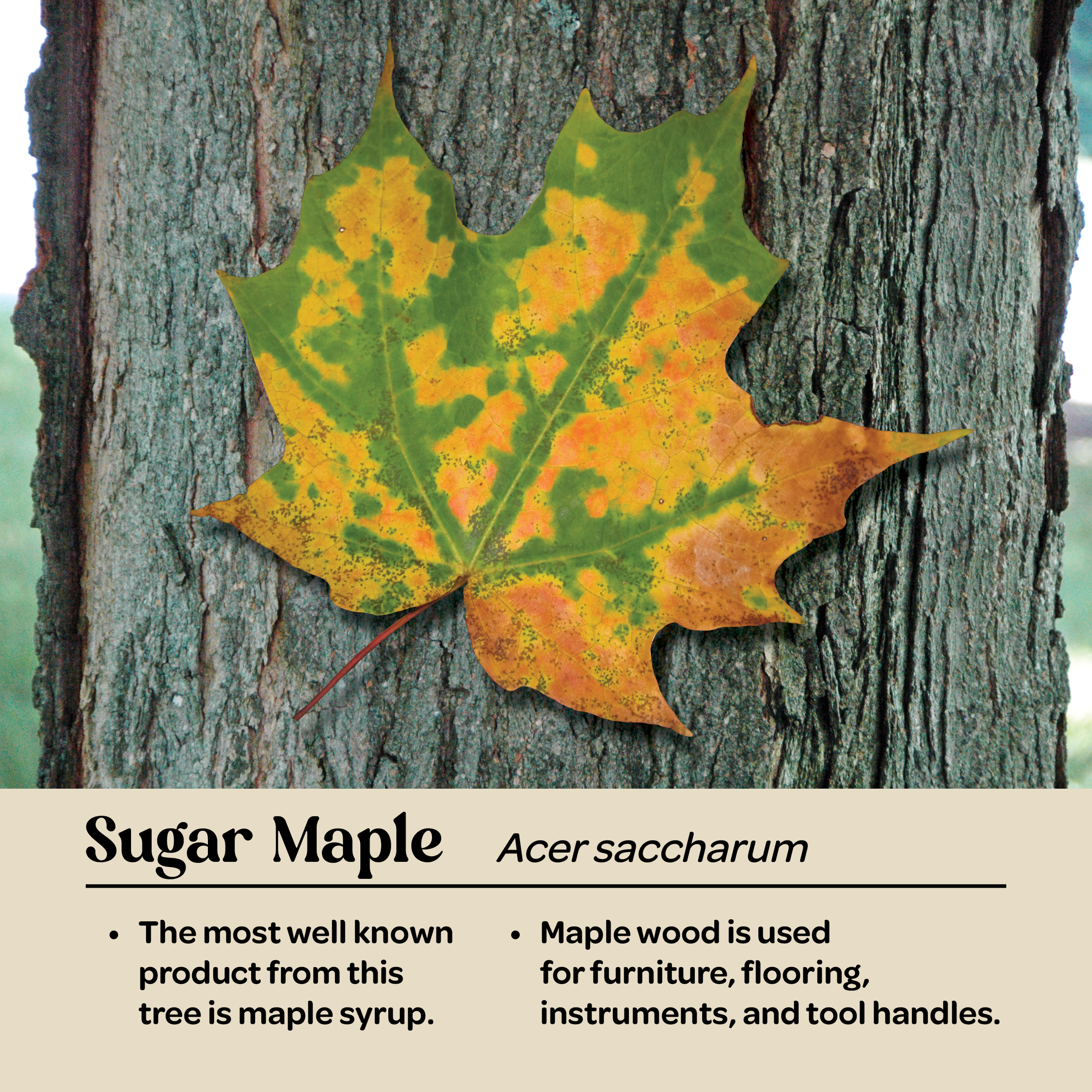

Scroll through a few trees that populate our area below!

Music and instruments

The traditional music of the AFNHA region reflects the cultures and heritage of the region. It easily migrated here in people’s minds as early settlement began, being passed on in the oral tradition. The genre most closely associated with Appalachian music is colloquially called “old-time music”. Old-time predates the recording industry, which gave the genre its name. This music is a foundation for many popular genres today, including country, folk, bluegrass, and americana.

Influence of the Recording Industry

Appalachian music is often perceived as “white” even though the foundations of this music heavily relied on White, Black and Indigenous people. The recording industry helped to homogenize music and spread it to a broader audience. Starting in the early 1920’s the recording industry segregated their productions into “hillbilly” and “race” records as part of a marketing strategy. Companies promoted blues and jazz-influenced styles to Black people, disregarding their considerable string band tradition. Blues came to be known as Black folk’s music and old-time came to be known solely as White folk’s music.

Traditional Instruments

Banjo

In Appalachia, many white musicians learned how to play the old-time downstroke style of banjo playing as well as banjo tunes directly from Black musicians. Banjo playing became integrated with the fiddle traditions of the Scots-Irish and Anglo settlers, cementing the banjo as an integral element of Appalachian old-time music.

Banjos are descended from West African gourd-lutes. Until the Victorian era, banjos were exclusively considered a Black slave tradition.

The banjo became popularized in White America through minstrel shows. By 1840, banjos were being made commercially and soon became popular in middle and upper-class homes. Mail-order catalogs made these previously hand-made instruments more accessible throughout the country.

Fiddle

West Virginia’s rich fiddling tradition can be heard throughout the AFNHA region. Fiddle music can be found in a variety of settings, in private homes, community events, dances, and the competition stage. Traditional fiddling is heavily influenced by the groups that brought the instrument to America, mainly Scots-Irish and Northern British settlers.

Fiddles in the mountains were primarily handmade until cheaper factory-made instruments were made available towards the end of the 19th century. Before the boom in factory-made instruments, it was common for children to begin playing on homemade fiddles made from cigar boxes, cornstalks, and gourds.

Dulcimer

The Mountain Dulcimer is known by many names, including “lap dulcimer”, “hog fiddle”, “fretted dulcimer”, and simply, “dulcimer”. Dulcimers are of German origin, being adapted from a type of zither, called the scheitholt.

While originally used for slower hymns, as the physical form of the instrument changed, so did the music that was played on it. The dulcimer was adopted by other ethnic groups, frequently being used for faster dance tunes.

Regionally, dulcimers never attained the popularity of the fiddle and banjo. Post-WWII folk revivals increased the popularity of the instrument nationwide.

Mandolin

Mandolins were brought to the U.S. by southern European immigrants. Originally, mandolins had rounded backs, earning them the name “taterbugs”. The design of the more familiar flat-backed mandolin was inspired by violin construction.

Mandolins were not very common in the AFNHA region or in its traditional music, until the instrument was embraced by modern bluegrass musicians.

Guitar

Guitars are one of the more recent additions to the traditional music of the region. Guitars were much more difficult for people to build themselves than banjos, fiddles, and dulcimers. In the 1920s, guitars started gaining popularity as rhythmic backing instruments for both other lead instruments and singers. Guitars, along with banjos, fiddles, and mandolins, became part of the standard model of Bluegrass bands with the genre’s creation in the 1940s.

Ballad Singing

The ballad singing tradition was influenced by lyrical traditions of settlers from the British Isles, work songs of African slaves, and common church hymns. Ballads are long, unaccompanied story-songs. The stories are meant to teach lessons to the listener and sometimes commemorate events such as murders and tragedies. Singers would often change lyrics to better suit their personal storytelling, causing variants to evolve.

Water Drum

The water drum is played by several Native American nations from this region. Construction and tradition varies between groups, but forms of water drums are present among Seneca, Shawnee, Lenape, and Tuscarora nations. Water drums are generally wooden vessels with tanned hide stretched across to create the drum head. The drum is filled with water, the amount inside affects the pitch and volume of the drum.

Music Today

The music in the AFNHA region today is just as varied in genre and instrumentation as anywhere else. Modern technology makes it easier than ever to share music and find inspiration across the globe. As technology continues to advance, younger generations and creatives continue to be influenced by other genres and cultures, innovating and creating new forms. Even so, the traditions persist and the roots of traditional music still run strong through these mountains.